Fiction – paperback; Granta; 104 pages; 2014.

Earlier this year I read Cynan Jones’ extraordinarily powerful novel The Dig and was so impressed I quickly sought out his first book, The Long Dry, which was published in 2006 and won a Betty Trask Award the following year. Cut from similar cloth as The Dig, it depicts a world that is earthy, rough and rugged but it is written in such lyrical pared-back language it practically sings with the beauty of the rural landscape in which it is set.

A lost cow

Set over the course of a single day, it tells the tale of a farmer looking for a missing cow. But this is much more than a simple search-and-rescue mission, for as Gareth searches the parched fields we learn about his hopes, his dreams and the love he has for his wife and children.

Central to this is Gareth’s connection to the land — he is a second generation farmer, having inherited the farm from his father who bought it after the war because he no longer wanted to work in a bank — and his community, including Bill, the simple-minded neighbour who was given a few acres of the farm by Gareth’s father, for whom he feels responsible.

We also hear from the wife — in brief, first-person snippets — who is worried that she’s no longer sexually desirable, suffers headaches and depression, and has a dark secret of which she is very much ashamed.

Then there’s the teenage son, who’s more interested in having fun than carrying out his tasks in any kind of responsible way, and the young daughter, Emmy, wise beyond her years and very much-loved and doted on by her father.

And finally, the lost cow’s wanderings — she is heavily pregnant, which is why it is so important for Gareth to find her — are threaded into the narrative, which is punctuated by little fragmentary set pieces, mini-stories within the story, that showcase life and death on the farm.

Nature writing

The Long Dry is very much a paean to nature, which is beautifully evoked in simple yet vivid descriptions, occasionally using unexpected words that not so much as confront the reader but check that you’re paying attention:

Damselflies and strong white butterflies, delicate as hell, are everywhere around the pond, and machine-like dragonflies hit smaller insects in the air as they fly. The reeds are flowering with their strange crests and on the island in the middle of the pond the willow herb is starting to come to seed, and the thistles.

There’s also some unexpected humour, too:

People are seduced by ducks: by their seeming placidity. They fall for the apparent imbecility of their smiles and their quietly lunatic quacking. But they are dangerous things which plot, like functioning addicts. In the local town — a beautiful Georgian harbour town which is not lazy and which is very colourful — the ducks got out of hand. […] If you tried to drink a quiet pint on the harbour the ducks were there and they sat squatly and looked up at you and seemed to chuckle superciliously, which was off-putting. If you put your washing out, somehow the ducks knew, and by some defiance of physics managed to crap on it. And duck crap isn’t nice. It’s green like baby-shit. If you fed a baby on broccoli for a week.

But mostly this is a tiny book packed with startling little moments and quietly devastating revelations — mainly about the farmer’s wife and the couple’s young daughter — that come out of the blue and turn the entire story on its head.

The Long Dry is beautiful and sad, poignant and often quirky, but full of human empathy. It constantly spins and shimmers and dances along the very fine line between sex and death — this book brims with both — and the way in which we are all essentially animalistic, in our basic needs, our desires and our behaviour. It explores the fragility of life, of holding on to happiness and how tragedy can strike at any moment. And it’s filled with vivid, sometimes unsettling, imagery that lives on in the mind long after the book has been put down.

It is, quite frankly, an extraordinary achievement to do so much in such a slim volume. I’ll be holding on to this one to read again…

I definitely want to read this

LikeLiked by 1 person

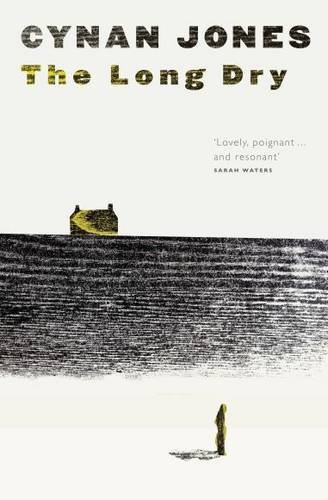

Sounds like a read for me. Great spare cover too (I know that is not how to judge a book, but…)

LikeLike

The cover is lovely, isn’t it? Granta has republished his three books in the same kind of livery, making for a handsome-looking trio, perfect to give as a gift to a bibliophile me thinks.

LikeLike

I think Cynan Jones’ writing is wonderful. The countryside he depicts is beautiful yet raw and stark – a far cry from the rural idyll of glossy magazines. I think I’m now up to date with his novels but I’m going backwards and forwards with them – The Long Dry was the last I read – http://www.ourbookreviewsonline.blogspot.co.uk/2015/02/the-long-dry-by-cynan-jones.html

LikeLike

Agreed: he’s a superb writer. His prose is quite musical (it reminds me of a lot of Irish writing) and I love his honest and heartfelt descriptions of the countryside and rural living.

Thanks, too, for the link. I’ll pop over to see what you wrote.

LikeLike

This sounds like an interesting book to read with Australian eyes. Here cattle are farmed in monstrous herds and the idea of a farmer spending a day looking for just one is bizarre because they range far and wide over vast spaces. (Would they even notice that one was missing, if they weren’t actually mustering? And if they did, and it mattered, they’d probably hunt for it in a helicopter or light plane, or on a motor bike.)

So the idea of a farmer having such a close connection with his cow is a reminder about the real value of livestock, as individual sentient animals. Of the intrinsic value of animals farmed like this, and why sometimes, paying more for less meat, is a good thing to do.

LikeLike

Hmm… I grew up in a farming community, and yes, those farmers would know if a cow went missing, especially at calving time. As a rookie journalist I also covered lots of agricultural stories and knew lots of farmers, mainly dairy but a few beef, and you’d be surprised at how well they know the animals in their care; the herd might be 300+ but they will know them all individually. Perhaps you’re thinking of the big cattle stations in the outback, where beef farming is done on a much bigger scale? Even then, I think those farmers would know…perhaps not straightaway but they do regular stock takes because they need to account for every head and make sure no one’s stealing them (cattle rustling is still a problem, I believe). And that kind of free-range beef is surely better than grain-fed mass-produced beef where cattle are confined indoors (which happens in the States)?

But back to the book 😉 I do think Cynan Jones has written a terrific novella. There’s just so much in it. And I’m still thinking about it two weeks down the line…

LikeLike

Yes, I was thinking of the big cattle stations in the outback, not dairy herds down Gippsland way where yes, I think they would know them.

One of my Facebook friends keeps posting horrific photos of outback cattle starving in the drought… it’s supposed to make me feel sorry for the farmers, but I feel sorry for the cattle, because those farmers know damn well that drought is seasonal, and that they’re occurring more often, so they know well before it happens that their animals will be suffering. For this reason I don’t’ eat beef at all if I can avoid it.

LikeLike

I’m so pleased to see that this one is good too. I’ll give it try at some point.

LikeLike