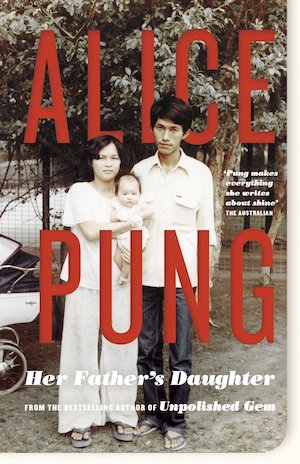

Non-fiction – memoir; Kindle edition; Black Inc; 254 pages; 2013.

It seems fitting to review Alice Pung’s memoir Her Father’s Daughter on the 44th anniversary of the end of the Cambodian Civil War (17 January 1968 – 17 April 1975) and the beginning of a new deadly period in Cambodian history.

When the war ended, the Communist Party of Kampuchea (aka the Khmer Rouge) took power. During its four-year reign, the Khmer Rouge arrested, tortured and executed more than a million citizens in what is now known as the Cambodian genocide. (Around a million more died of disease and starvation.)

Alice Pung, an Australian-born writer, editor and lawyer, is the daughter of two Cambodians who fled the killing fields of the Khmer Rouge. Her parents sought asylum in Australia in 1980, and this memoir charts Alice’s early adulthood when she unearths the story of her father’s frightening past and comes to understand some of his peculiar, over-protective behaviours.

A startling story

Her Father’s Daughter is a startling and often beautiful story, grim in places but also warm and funny and heartfelt — and totally engrossing.

Unusually for a memoir, it is written in the third person (perhaps, I suspect, to provide some emotional distance for the writer), which lends it an other-worldly, almost fictional, feel.

Her father had named her Alice because he believed this new country to be a Wonderland, where anything was possible if only she went along with his unfailing belief. His patriotism rang truer and more annoying than any bogan supremacist’s. ‘Australians all let us rejoice, for we are young and free.’ This to him was the most beautiful national anthem in the world. There was golden soil and wealth for toil. Who wanted to be anywhere else? In other countries, where their anthems were all about rinsing the land in blood of the brothers?

It examines Pung’s growing realisation that her father has been deeply traumatised by past events at the same time that she, herself, is trying to stand on her own two feet as a young independent woman. Keen to forge out on her own, she’s often annoyed by her father’s meddling, his inability to understand her need to travel and explore the world, his hurt when she won’t heed his advice to settle down and get married, to eschew a potential career in law for one helping him run his Retravision store.

To live a happy life, he believes, you need a healthy short-term memory, a slate that can be wiped clean every morning, like one of those toys he bought for his daughter when she was young – an Etch A Sketch. If you turned it upside down and shook it, your art disappeared.

It’s only when she begins to dig into her father’s story that she is able to understand that his fears for her future and her happiness come from a very dark place. She travels to China and Cambodia, meeting family members and other survivors, and hearing their harrowing tales of deprivation, torture and survival.

There is a lot of death in this story, but there are funny moments too. Pung paints her father as a quirky character with odd character traits, but she does so with fondness and respect. It reads very much as a love letter to him.

And the prose, so astonishing in its clarity of thought and vision and honesty, in its preparedness to discuss difficult topics, is often wry and always original. Her sentences have a dark beauty to them, as these examples show:

His parting gift was a pomegranate from his travels. He gave her an orb of perfect seeded gems encased in incarnadine, but inside her ribcage was rotting fruit.

And:

She didn’t feel too independent. There had been hours of loitering alone, feeling lost, feeling like there were feral kittens fighting in her solar plexus.

And:

The skies were clear then too, and the stars winked like unforgiving blades.

Courageous tale

I really loved this story, for its honesty, its courage, its inspiration and its love. In exploring her own Asian roots and telling her father’s own troubled history, Pung has crafted a powerful story about tenacity, family heritage, intergenerational trauma — and hope.

Her Father’s Daughter was shortlisted for numerous awards in Australia and won the Non-Fiction Prize in the 2011 Western Australian Book Awards.

For another take on this book, please see Karenlee Thompson’s eloquent review, which has been posted on Lisa’s blog.

If you liked this, you might also like:

‘First They Killed My Father: A Daughter of Cambodia Remembers’ by Loung Ung: an emotionally wrenching memoir about Ung’s traumatic childhood under the Khmer Rouge.

This is my 15th book for #TBR40 and my 8th book for #AWW2019