Non-fiction – hardcover; Black Inc; 96 pages; 2024.

In recent years I’ve become a fan of Black Inc’s Writers on Writers series in which “leading authors reflect on an Australian writer who has inspired and influenced them”. I have previously reviewed volumes on Tim Winton, Helen Garner and Kate Jennings, and have many more in my TBR. They are excellent “deep dives” into writers who have shaped, and continue to shape, Australia’s cultural discourse.

The latest in this series is about Kim Scott, a Noongar writer who has won the Miles Franklin Literary Award twice — for Benang, from the Heart (2000) and That Deadman Dance (2011) — and is Professor of Writing at Curtin University in Western Australia.

Pathway to truth

In this perceptive and highly engaging essay, Tony Birch (who also has Aboriginal ancestry and is a qualified historian) discusses Scott’s novels to “explore fiction as a pathway to truth”.

In the 2020s, with ‘truth-telling’ becoming both a demand from Aboriginal people and, perhaps unfortunately, a populist buzzword, Kim Scott uses storytelling to address truths of the past that some would prefer we left silent and undocumented. (page 15)

He shows how Scott’s work has taken on the difficult questions about Australia’s past and interrogated them from a Noongar perspective.

Fiction, of course, also produces stories of national unity, whitewashing and occasional flag-waving. I value Kim Scott’s fiction so highly because I feel that his approach to fiction is to put the flags aside. (page 24)

Birch argues that Scott’s award-winning novel That Deadman Dance is not a novel of reconciliation, for instance, but a story that shows us “who we could be, collectively, in the future”.

Similarly, he suggests that Benang is a story that shifts our “collective understanding of who we are as a nation, both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal”. That’s largely because his work helps us see that history is a bumpy road and not always linear and that the course of colonial justice in Australia is perverse.

Exploding national myths

He is not afraid to bust open white Australian myths of its colonial past and show how the nation is built on land theft and violence, much of it swept under the rug.

His most recent novel, Taboo, set in modern-day Western Australia, wrestles with truth and reconciliation when the nation seems reluctant to address the violence of the past.

But while his writing might be driven by anger, it is always balanced and generous. It is not about victim blaming or sensationalising events, it is simply laying it out, warts and all.

Kim Scott is a gentle combatant fighting injustice. And he is on our side — each of ours. Scott uses words, sentences, images and stories to confront racism, a blight that for him ‘burns like a pox and a plague and is incubated at the centre of how we live and organise ourselves.’ (page 32)

Power of fiction

On Kim Scott is an excellent, short book on the power of fiction to undermine falsehoods and to flesh out the truth in ways that evoke empathy and understanding. Or, as Birch so eloquently puts it, “to consider this country’s past in a mature and ethical manner”.

More importantly, while this book is about a singular Australian writer, it’s also a fascinating portrait of us as a people. It’s also an excellent clarion call about the need to come to terms with the past so that we can build a brighter future together.

If we are to shift the nation’s psyche for the better, we must embrace stories of our colonial past, rather than bury them. And if we are to overcome discriminations embedded in contemporary Australia, we will need to tell new stories. This is the work that Kim Scott has been doing for many years, and we are in his debt. (page 79)

Here, here.

Book launch: Kim Scott’s ‘Benang: From the Heart’ 25th-anniversary edition

On Friday night, Fremantle Press launched the 25th-anniversary edition of Kim Scott’s groundbreaking novel Benang: From the Heart at the Walyalup Civic Centre.

Local author Molly Schmidt, who is one of Scott’s past students, interviewed him about the book, including how he came to write it and why.

He said he wrote it as a form of “channelled aggression” after becoming increasingly angry at the injustices suffered by his people. He wanted to express that anger in a way that did not “dwell on or sensationalise” the trauma but “speak about it straight”.

He had come across A.O. Neville’s^^ Australia’s Coloured Minority: Its Place in the Community — a book, published in 1947, that documents racist colonial beliefs — in which he saw a photograph of three generations of Aboriginals, each one lighter skinned than the next, to depict how Aboriginal blood could be diluted to “breed them out.”

Scott identified with the lighter-skinned individual and wanted to explore Neville’s deeply offensive pursuit — to create the “first-born-successfully-white-man” in the family line — and to explore how his colonial settler dogma had harmed Noongar culture, language and family.

He said he played with “language from the archives” which he considered to be “profoundly hostile” and used dark humour to lighten the load.

It was a privilege to listen to the discussion — he clearly has a great rapport with Schmidt, who was warm and generous but also unafraid of asking delicate questions — and to hear him read from sections of the book. He has a remarkably entertaining reading voice and animated style. If you ever get the chance to hear him read, clear your diary to attend!

An interesting fact from the discussion is that we’ve all been pronouncing “Benang” wrongly. Scott pronounced it as “Ben-ung” (to rhyme with “hung”).

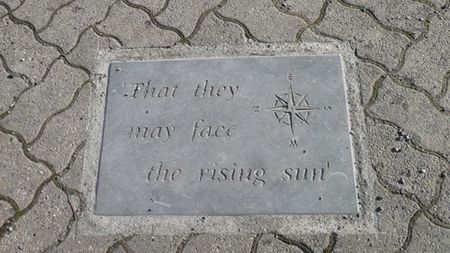

Fittingly, we also discovered that Benang means tomorrow.

^^ Neville was Chief Protector of Aborigines in Western Australia from 1915 to 1936 and Commissioner for Native Affairs from 1936 until his retirement in 1940. He is a recurrent figure in much First Nations literature.